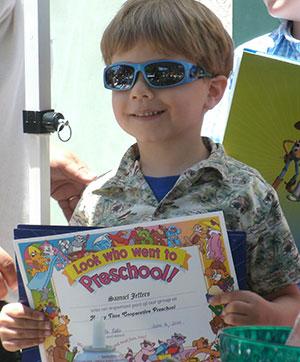

Sam Jeffers was about to start second grade when he first experienced symptoms that turned out to be caused by a thalamic glioma. His mother, Sabrina Jeffers, tells his story.

Before his diagnosis Sam was a reader, writer, and artist. Lover of swimming, playing at parks, and listening to music. He was a tree climber and rock scrambler. And a great cook. His imagination was huge, and that was revealed in his writing, drawing, cooking and play. Math came easily to him, and his reading was consistently above grade level. He was always a favorite of grownups because he could hold a conversation with them—he kept his listeners engaged.

In mid-August 2012 Sam began to complain of having "funny feelings" in his legs. Usually this followed him having sat on his knees for long stretches, so we figured his legs had fallen asleep from lack of circulation. We told him not to sit that way.

After he started second grade, he reported a few times that he had fallen at school, but didn't remember falling. For example once he said at lunch he ended up under the lunch table and didn't know why but kids were laughing at him.

On September 18 a P.E. assistant witnessed Sam fall to the blacktop and have a seizure. We saw his pediatrician the next day. His pediatrician made a referral and scheduled an MRI and told us not to worry—99% of the time this is nothing.

On September 20 Sam came to me during my afternoon recess duty (I was a first-grade teacher at Sam’s school that year) to tell me that he had another "funny feeling" at P.E. that day. This time he had wet his pants—a sure sign of a seizure. I brought Sam to the office and called his dad. John took Sam to the ER, while I finished out my school day.

When I arrived at the ER Sam was having an MRI. Some blood work had been done, and an EEG, and then a chest X-ray. Then we waited. I wasn't worried. I figured it was epilepsy and we could handle that.

Unfortunately, we were wrong. The MRI revealed a growth on Sam's thalamus—a glioma, the ER doc said. Dr. Young made arrangements for Sam to be evaluated at Children's Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA), and to be transported there via ambulance. I really can't tell you how I felt at that point. The same feeling that was to be repeated with every post-MRI doctor visit. I felt sick, numb, weak, powerless.

The only thing Sam, precocious beyond his seven years, said was: "Is this life threatening?" Dr. Young answered him honestly—yes, many things can be life threatening, but we can treat people.

I rode in the ambulance with Sam for the 3+ hour trip to LA. We arrived at CHLA and were assigned a room and a nurse and essentially went to bed. Every four hours through the night (and for days to come) Sam was evaluated by a neurologist.

The next morning we met with neurosurgery. The head neurosurgeon told us there was nothing that could be done for Sam. We were told he would certainly die from this, as they could not operate on this part of the brain given the nature of this tumor. We were not told how much time he had, but that we should prepare for the death of our son.

As quickly as that, our world had been turned upside down. But we had to remain strong for Sam, and try to keep things as “normal” as we could as we faced this new reality of ours.

We rounded out the day, this pre-Shabbat day, by playing on the outdoor playground; welcoming our other two children, my mom, and aunt to the hospital; talking with our rabbi; and hosting a Friday night service in our room. I don't know how I held it together as I heard mishaberach for the first time said for my child. Just as we finished our service, just as the rabbi said, “There isn't enough wine in the world," oncology came to see us.

Dr. Brown took John and me to a small meeting room down the hall and described how although the tumor could not be removed, he believed it could be treated. It was a low-grade (grade II) tumor, so it was slow growing. He didn't promise us a cure, but he thought he could give Sam time—as in years. Dr. Brown described a weekly outpatient chemotherapy that would last 18 to 24 months. He said that John and I would return to work, and Sam would return to school. Aside from those weekly trips to the hospital, and daily meds to keep seizures in check and infections in his port at bay—Sam would live a normal life. In case the chemo didn't work he also described all the many treatment options (radiation, other chemo drugs, clinical trials) that we would have at our disposal. He gave us hope. We returned to the room jubilant.

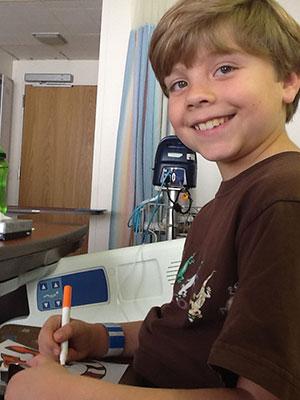

In the days that followed there were more MRIs, an EEG (finally saw my first seizure) and a surgery to insert Sam's port-a-cath. On Tuesday, September 25, Sam had his first chemo. The next day we went home with instructions to return in a week for more chemo.

From September 25 until late April 2013, Sam received two alternating chemo cocktails: vincristine and carboplatin, alternating with irenotecan and temozolomide (a daily pill). He had an MRI on December 26 that showed no change, and another in mid-April that revealed some growth and a change in the tumor from low grade to "medium" grade. Chemo was changed to vinblastin, which was supposed to work well on these medium-grade tumors. Vincristine and carboplatin had made Sam a little nauseated, but the irenotecan made him really sick—puking, cramping, and diarrhea. Temozolomide dropped his white blood cell and platelet counts so low we had to take a few weeks off of treatment from time to time. The vinblastin had virtually no side effects. He didn’t lose his hair yet. He had amazing hair.

Throughout this period Sam's only symptoms were seizures (which were controlled by Keppra), and a tremor in his left hand. He missed school once a week but maintained good grades in all subjects and continued to learn as I would expect an advanced student to learn. I continued to work, missing a day every week or every other week depending on the chemo course Sam was on. Sam took his meds with very little complaint, and except for getting poked actually seemed to enjoy the weekly road trips to Santa Barbara or Los Angeles. Sam was always a favorite of doctors and nurses.

In early May, Sam seemed foggier than usual, started to have some trouble with balance, and began to have seizure warnings (which had all but disappeared once he started on Keppra in September). His oncologist was concerned and was considering moving up his MRI which was scheduled for July. On May 25 Sam had a seizure for the first time since early October. An MRI was scheduled for Wednesday.

That Wednesday, May 29, MRI showed the original low-grade tumors had grown beyond the thalamus towards the front of Sam's brain (explaining the fogginess and seizures), and a new high-grade tumor appeared at the back of his brain. Radiation was no longer an option because the tumors were too massive and where they were in the brain would cause too much collateral damage. There were no clinical trials open for this particular type of tumor.

Dr. Brown said there was nothing more he could do for Sam. He suggested a chemo that might shrink the tumors a bit to buy us some more time with him. At most he thought that might work for a few months. Then Sam would need palliative care for pain, and he would die. Dr. Brown made referrals to hospice. We elected to begin Sam on the non-curative chemos avastin and etoposide immediately following the May 29 MRI. He didn't return to school, and I did not go back to work.

On June 2, Sam had a massive three-hour seizure requiring a visit to the ER via ambulance. As a result of that seizure his oncologist placed him on steroids and increased his Keppra. The steroids caused him to gain at least 25 pounds. He began to lose his hair during this chemo course, as though cancer wanted to take one last insulting jab at him.

Soon afterwards, Sam began using a wheelchair. He stopped being able to dress himself or bathe himself or go to the bathroom by himself. His thinking and speech became incredibly slow and eventually he could no longer talk at all. He stopped being able to eat or drink. Then, on October 20, 2013, under a full moon hovering above the couch in our living room, Sam died surrounded by his family. He was eight years old.

As parents we want the best for our children. We have so many hopes and dreams for them. And we want them to be happy, as children should be. When a parent hears those words “Your child has cancer,” everything changes. We don’t want any other child or family to go through what Sam went through. We want to help find a cure for these rarer types of tumors that cause so much devastation in the lives of children. That’s why we strongly support the incredible work and efforts of Dr. Mark Souweidane and the Weill Cornell Children’s Brain Tumor Project. Together, we truly believe we can change outcomes for future families.

Sabrina and John Jeffers